Repairing Customer Onboarding Processes: A Case Study

“The ability to reflect on one’s past actions and envision alternative scenarios is the basis of free will and social responsibility.”

Judea Pearl

A couple of semesters ago Bob Albright and I took several of our graduate students in Business Analytics to service a consulting request from a pharma manufacturing firm. Bob is a Pompea College of Business colleague – an outstanding Professor of Management. The company that had invited us produced pharmaceuticals and sold its products nationwide, directly to independent drugstores, chains, and distributors. The Pompea College provides this service to the business community by way of offering real-world experience to our students.

The pharma company had brought us in because they were facing severe problems with their customer approval process. Approval wait-times had ballooned; they were losing prospective customers. Potentially good customers were giving-up and leaving in droves, tired of waiting for approval; customers were being rejected – and angered - by seemingly superfluous issues. Many of those alienated remained unclear as to how the company’s vetting process worked. Indeed, there was no clear path to compliance let alone a simple one.

There are (at least) two interesting developments that have afflicted onboarding processes generally, especially in the United States – over the last few years. First, things have gotten more complicated. Second, the costs of managing business relationships have increased.

There is an element of uncertainty involved in onboarding. A company does not want to enter into relationships that fail. It is costly to fail. And it appeared that the number of veto points and considerations overseeing the onboarding process in the company had increased significantly over the years. In yesteryear, concerns were primarily financial and reputational. Today, aside from reputational and financial issues, rapidly evolving cultural and societal norms and associated legislation now compel all firms to closely scrutinize violations of all sort of considerations including gender, sexuality, and race composition of the board, environmental, social and governance matters, safety, security, among others. Violations in any of these could derail any prospective partnership. Within firms, the number of in-house overseers of the review process had increased significantly: finance approved finance, diversity offices approved gender and race elements, the sustainability office examined green issues, public relations managed any number of other concerns.

This increased significantly the number of “veto points” - independent decisionmaker-managers who had the ability to derail a prospective client based on their limited frame. The divergence in preferences and incentives among senior and department managers led to a severe “principal-agent” problem. We introduced this concern into our model and found that it is possible to trade-off increases in a company’s pool - ie. a reduction in acceptance thresholds - by devoting careful attention to stamping out the fragmented decision-making process.

And speaking of model -in an interesting wrinkle, we were surprised when we examined the performance of the company’s current customer portfolio. Practically all their customers were “Successful.” There were no “Fails;” there was only One Class of customers. This is the result of two reasons -for the most part.

First, a firm’s “Success Ecosystem” is one of the intangibles at the root of many a managerial success. Both parties to the budding relationship want to make sure that the partnership works; companies invest considerable funds in building and maintaining relationships aimed at ensuring the longevity and soundness of their business relationships. This process allows for the quick identification of those companies who are “not going to make it.”

Second, and what is a rather common management practice nowadays – whereby an ongoing relationship with a customer is periodically scrutinized through a cost-benefit lens. Those customers who come out on the wrong side are politely “let go.” The reason is simple: the cost of servicing the account is not surpassed by the gains or even prospective gains.

To sort out the impact of these two managerial tweaks we would have to reconstruct the current-customers portfolio to reflect, at the very least, “Performing” from “Under-Performing” firms. Only then would we be able to determine the impact of any changes in onboarding.

We reconstructed the company’s customer portfolio using isolation forests. This is an unsupervised machine learning-based algorithm for reconstituting the binary composition of what are known as One-Class problems. A clustering-based algorithm that demonstrated a 91 percent accuracy rate in the simulation trials. The key assumption here is that despite customers in the portfolio showing as Performing – there is an implicit ranking whereby the bottom x percentile should be considered non-performing – and the isolation forest routine was able to identify it.

Once the “true” customer portfolio was re-constituted we used it in a simulation of the firm’s onboarding process – which enabled us to understand the impact of alterations of firm parameters. We reduced all the features considered in onboarding practice to two features – coded as “Reputational Score” and “Compliance Profile” and subsequently scored all prospective and current customers on these two features. The covarniance between Reputational Score and Compliance Profile served as the proxy for the level of administrative dysfunction - that is to say - the “bite” associated with the embedded principal-agent problem they had: we called this Management Discipline. The greater the level of managerial discipline the less evident is the principal-agent divergence and the better functioning the firm.

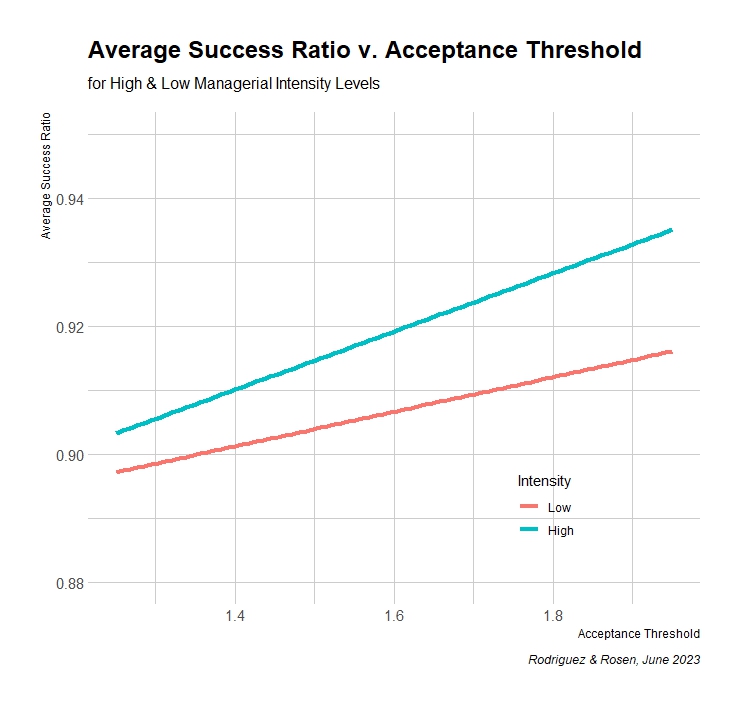

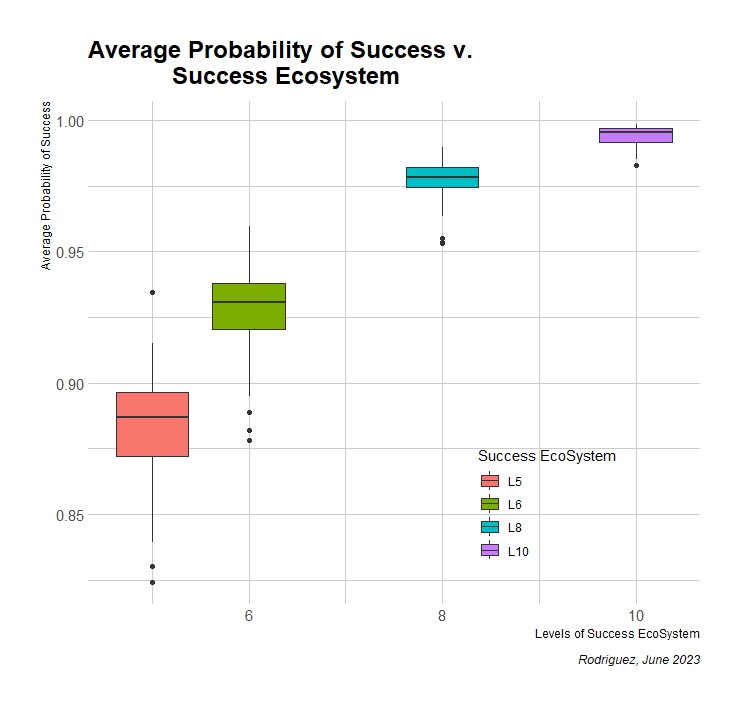

We gauged changes in the Acceptance Threshold, EcoSystem levels and Management Discipline on two Performance metrics: individual customer’s Average Probability of Success and the firms Success Ratio, the ratio of the number of Succesful firm to the number of new-customers accepted.

Figure 1 displays our strongest result: it is possible to reduce onboarding stringency and replace it with a focused effort at eliminating managerial decision-making fragmentation. The figure shows that the average success ratio decreases as more firms are accepted. The relationship improves with an increase in resources devoted to managerial discipline (the shift from the red to the blue line in figure 1).

We see a similar results with respect to the Average Probability of Success and resources devoted to Success Ecosystem. Note two things: (i) the variability of the probability of success stands to improve with more resources; and, (ii) Average Probability of Success increases but at a decreasing rate. This can be seen in Figure 2.

Ok, what of all this? First, the recommendations. All in all we had two lessons for our client. Reduce the number of approval veto agents by ascribing overall responsibility to one onboarding czar. That is to say – solve the principal agent problem. Second, it pays to substitute resources devoted to ensuring success in exchange for a larger pool of prospective customers – but gingerly.

Second, our method. Counterfactuals are hugely useful managerial strategy tools: they expand the scope of our understanding of events and allow us to see things which would otherwise remain hidden. With apologies to General Eisenhower, its not the plan – it is the counterfactual. And last, we were delighted to be able to show how to apply an obscure analytics tool to “reconstitute” a real customer portfolio clearly showing performance – a step which was key to the analysis.